Phishing: What are these menacing cyber attacks all about?

Getting Phished

Have you ever received a piece of postal mail (i.e. “snail mail”) that looks important but turns out only to be a coupon, marketing, or a sales pitch?

Most of us have probably encountered something like this: a letter that looks important – perhaps a check, government notice, or other official correspondence - but that turns out really to be something entirely different.

In this situation, the structure of the letter – its format, font, shape, and numerous other characteristics – have the potential to cause us to open it when otherwise, based solely on the contents, we would throw it in the bin.

What information do phishing emails fish for?

If you’ve had an experience like this, then you already intuitively understand “phishing”. Phishing is the systematic process of sending emails with the intent of obtaining private information.

This information could be

- financial account information,

- personal details (government-issued identifiers, address, etc.), or

- authentication information (usernames, passwords).

Phishing - A real-life scenario

A user receives an email purporting to be from their bank with a link to a “login” site that asks for their credentials. A seemingly-innocuous email message can also be a method of transmission for email-borne malware; for example in situations where email messages have an attachment that, when run, installs hostile or malicious software on the user’s computer.

Because the email looks legitimate, users - particularly more trusting users or those with less technical acumen) - may assume it is legitimate, thereby divulging sensitive data, authentication information, or personal details.

Just like the case of the postal letter that looks important (but really isn’t), an email that appears to be from a trusted company or service (but in reality is an attacker) leverages the form and features of the trusted email to assume legitimacy and thereby cause the user to respond in a way that puts them at risk to scams or fraud.

From this relatively straightforward and easy to understand the concept, a seemingly endless array of related attack types have emerged:

- spear-phishing,

- fishing & smishing,

- whaling,

- angler phishing and other related attacks have emerged that can make the situation confusing.

With this in mind, let’s take a deep dive into some of these related attacks, how they work, and how they’ve been used by attackers (Here's a resource that will navigate you through cyber security attacks).

The Phishing Template

The first phishing attacks were often fairly simplistic: a legitimate-seeming email from a company or organization that you trust containing a link to take action.

- A legitimate layout - for example - an email from a reputable bank (or so it seems) containing the bank logo, regulatory-mandated text at the bottom (e.g., disclosure or privacy statements),

- A reasonable-seeming call to action (for example, to update their contact information, read a customer service bulletin, verify a transaction, etc.)

- A link - perhaps one that (at a glance) looks like that of the purported sender - is included with the email, ostensibly for the convenience of the user in responding.

An example

This approach is potentially exacerbated by using “IDN homographs” - characters that, while different from each other, appear visually similar on-screen. For example, can you spot the difference in the following two URL’s?

Figure 1: Legitimate URL

Figure 2: IDN Homograph

The first image is of the legitimate URL for Adobe’s main website. The second uses a homograph of the letter b (in this case the letter b with a small dot below it, Unicode U+1E05.)

It is hard to tell the difference - many users might conclude that the dot under the b is a piece of dust or other debris on their screen rather than part of the URL. This example, in fact, was actually employed as part of a malware-spreading campaign in 2017.

Browser vendors have made such homograph obfuscation techniques more challenging to pull off (for example by disallowing combinations of character sets as in the example above), but realistic-seeming homograph attacks can still be created using a sole character set. By making the URL look legitimate, perhaps purposefully misspelling a legitimate domain, adding characters, using a different character set, or otherwise manipulating the URL, the attacker can create a realistic-looking, plausible-seeming URL that might fool an otherwise astute and vigilant user.

Spear-Phishing

As phishing attacks have become more prevalent and users have decreased their susceptibility to attacks of this type, attackers have had to up the ante on the verisimilitude of their attacks.

For example, emails filled with obvious typos, URL’s that contain obvious ambiguity, and even subtle differences in the “tone” of an email from a known source are less likely to result in a successful phish of many users.

In light of this, attacks have increased the specificity in how they address a user. They do this to make the email more believable, thereby increasing the likelihood that a user will succumb to their attack.

One manner to do so is through spear-phishing. Spear-phishing is, in essence, a phishing attack that targets a particular person, organization, corporation, or other entity.

Using information obtained through other means – for example a person’s social media page, a corporate blog, the information in public forums or user groups, or other data they can gather – to tailor the attack to increase the likelihood of the attack being believed.

In a spear-phish, a user might receive a message referring to events that they participated in (obtained via examination of social media presence) or other more tailored contextual information. The differentiation in a spear-phishing attack is the targeted nature of the attack.

An example

One notable example of a successful spear-phish involves the compromise of John Podesta’s emails during the United States 2016 election. In this case, Podesta (at the time the chair of the Hillary Clinton campaign) received an email that appeared to be from Google notifying him of a compromise of his account credentials. Instead of really being from Google though, it was actually an email from a hacker group (subsequently attributed to one of Russia’s intelligence services) leading to a “login” page that asked for, and subsequently harvested, login credentials.

Whaling

A spear-phishing campaign, as you might imagine, is difficult for an attacker to pull off at scale. Why? Because each individual spear-phish needs to be tailored. A spear-phish that has been heavily tailored to work for organization A is less likely to be successful in organization B.

In fact, the more tailored the spear-phish, the less adaptable it is likely to become. Because of this, attackers have shifted to target larger, more affluent organizations in an attempt to maximize their return (i.e., to maximize the amount of money the can extract from each victim). The term “whaling” then refers to methods of attack that specifically target “whales”: large, affluent, potentially high-profile individuals and organizations that can be fleeced for a large dollar amount.

An example

Specific techniques like Business Email Compromise (BEC) can be employed, which involves sending a message that appears to be from a coworker or superior (e.g. the CEO or CFO) requesting a high-dollar wire transfer (usually with an imminent “deadline”). For example, Xoom (a large funds transfer provider) reportedly transferred 30.8 million dollars to attackers as a result of fraudulent emails of this type.

SMishing and Vishing

In addition to email, other services such as SMS, Voice over IP (VoIP), or other channels can be employed in similar attacks. “SMishing” involves the use of SMS (text messages sent over the celluar network) that purport to be from a friend, coworker, or organization with the intent of soliciting user details, obtaining credentials, or otherwise obtaining access they shouldn’t.

Like emails, it can be challenging for a user (particularly one that isn’t technically astute) to evaluate the legitimacy of a text; consider how often you get notifications from your bank, credit card companies, or other services that you use.

If you received a text from a number you didn’t necessarily recognize – but that referenced something that might or could be true (information about a shipment being sent to you, an invoice, or use of a credit card for example), it might be tempting to follow an included link to learn more and evaluate the message.

Likewise, VoIP can be used as a mechanism to attempt to gather data about you by an attacker – or to cause you to download and run malware or attachments. In this case, you might receive an unsolicited VoIP call from someone claiming to be a coworker or other employee of a large organization. In light of a call like this, someone might let their guard down and thereby become a victim of an attack (also consider checking out this career guide for data science jobs).

Angler phishing

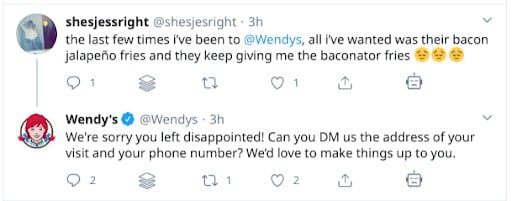

The last one we’ll look at in depth is a relatively recent one: “angler phishing.” In this case, an attacker will impersonate the customer service apparatus of a large organization on social media to respond to those discussing an experience they had over social media channels. In many cases, because marketing-savvy organizations do engage with customers through social media channels, attackers can use similar-looking social media accounts to attempt to impersonate those organizations.

An Illustration

As an example of how this is possible, consider this exchange between a customer and Wendy’s (a US-based fast-food chain) and a customer:

Source: Twitter.com

The customer, discussing their experiences, might receive a social media interaction from the business in question. Very often, this can take the form of reimbursement or compensation for a bad experience. But consider the fact that other accounts - not necessarily those affiliated with the business itself - can ape the style, tone, and even handle or profile name of a customer service social media presence. For example, compare the visual markers (picture, handle, etc.) with a parody account not affiliated with Wendy’s:

Source: Twitter.com

Note that I’m using this example not to imply that there’s a link between this particular parody account and angler phishing, but instead to illustrate the point of how the visual cues from a social media account can appear similar to another.

In this case, the account is clearly a parody and not affiliated with Wendy’s in any way: it says so clearly and unambiguously in the description (note the text stating it is “Not affiliated with Wendy’s”.) However, the visual cues used by this parody account appear similar to the legitimate Wendy’s social media presence.

In angler phishing, an attacker will exploit this not to bring about levity and parody but instead to glean information from those they engage with.

Another example

Consider an attacker who creates an account with a similar handle as a business, using the same or similar visual cues as that business (identical image, link to the website, etc.).

Were such an account to respond to a customer’s experience, requesting a DM (direct message) to obtain information from that customer (perhaps a phone number, name, address, or other details), a non-tech-savvy user or one unfamiliar with the real social media presence of the business might acquiesce to the request.

From there, the attacker can request further details, ask them to download or run a utility, or otherwise trick the user into taking action that benefits the attacker.

Meaning, the user might assume that the real-looking (but fraudulent) request is an official one: one operating under the banner of the business. In order to receive the benefits from the “customer service team” looking to make up for the bad experience the customer had at their business, they might divulge personal information in a way that puts them at risk.

Prevention

Of course, for the practically-minded security practitioner or an individual who wishes to remain protected from attack, the more salient question is not what these attacks are but instead how to prevent them.

For individuals, a healthy dose of skepticism for anything received on the Internet or any other communication channel (be it email, web page, VoIP, SMS, etc.) is a useful first line of defense. Users should remain skeptical of any request – no matter how legitimate-seeming – for personal data, for financial information, to download and run software or execute attachments, etc.

For organizations, these are useful measures of course, but it can also be helpful to employ the help of simulation tools in combination with user awareness training. Meaning, train users on phishing: what it is, how attackers employ it, and pointers about how to tell a phishing email from a real one. Phishing simulation involves sending phishing-style emails to employees, to find where users may need additional training or where they are otherwise susceptible to phishing-style attacks.

Quarantined? Become a certified cybersecurity professional without stepping a foot out of your home.